Either way, after helping solidify the direction of Television alongside Tom Verlaine and subsequently an early line up of the Heartbreakers, Hell went off on his own to write one of the definitive songs of the initial wave of punk stuff. “Black Generation,” although endlessly interpreted in different ways, remains a readily identifiable landmark in the genre’s develop, both musically and lyrically. Basically, it’s just good stuff.

Of course, Blank Generation, the album and the song, will probably continue to be discussed when future generations attempt to figure out why punk happened where and when it did. But then, probably, everyone’s gonna wind up wondering why Hell’s follow up was such a dramatic departure in quality, tone and vision.

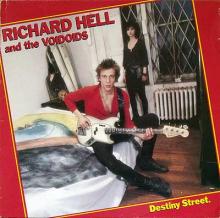

Again, considering is contributions to Television, the Heartbreakers as well as ostensibly working up Blank Generation in a vacuum, void of other like minded acts – not to mention his “Please Kill Me” shirt - is more than enough to ensure his legacy. But that was all done by 1977. And five years later, in 1982, Destiny Street was released.

Part of what made Hell’s first album so incredible was Robert Quine’s guitar playing. Since the ’77 album being issued, the guitarist had gone on to work with Lester Bangs as well as Lou Reed on his Blue Mask album. Oddly, though, what made that Reed album one of the better lackluster releases since his Velvet Underground days, was Quine ripping a few nasty, almost atonal solos.

Hell, obviously, is a completely different type of singer, performer and writer than Reed. But by the time ’82 rolled around, Reed was something like two and half decades into his career. Hell had clocked a decade or so. And that’s really why Destiny Street’s lack of stand out compositions is so surprising.

Hell wrote poetry before, during and after his music career began. So, there not being anything approaching a memorable hook is just confusing. Between that and the apparent reigning in of Quine’s talents leaves the album a pretty bland historical document. The lone bright spot, oddly enough, is a late appearing cover of “I Can Only Give You Everything,” taking the Van Morrison composition and New Yorking it up a bit. A good addition to be sure, but not enough to save the disc from being pretty useless.